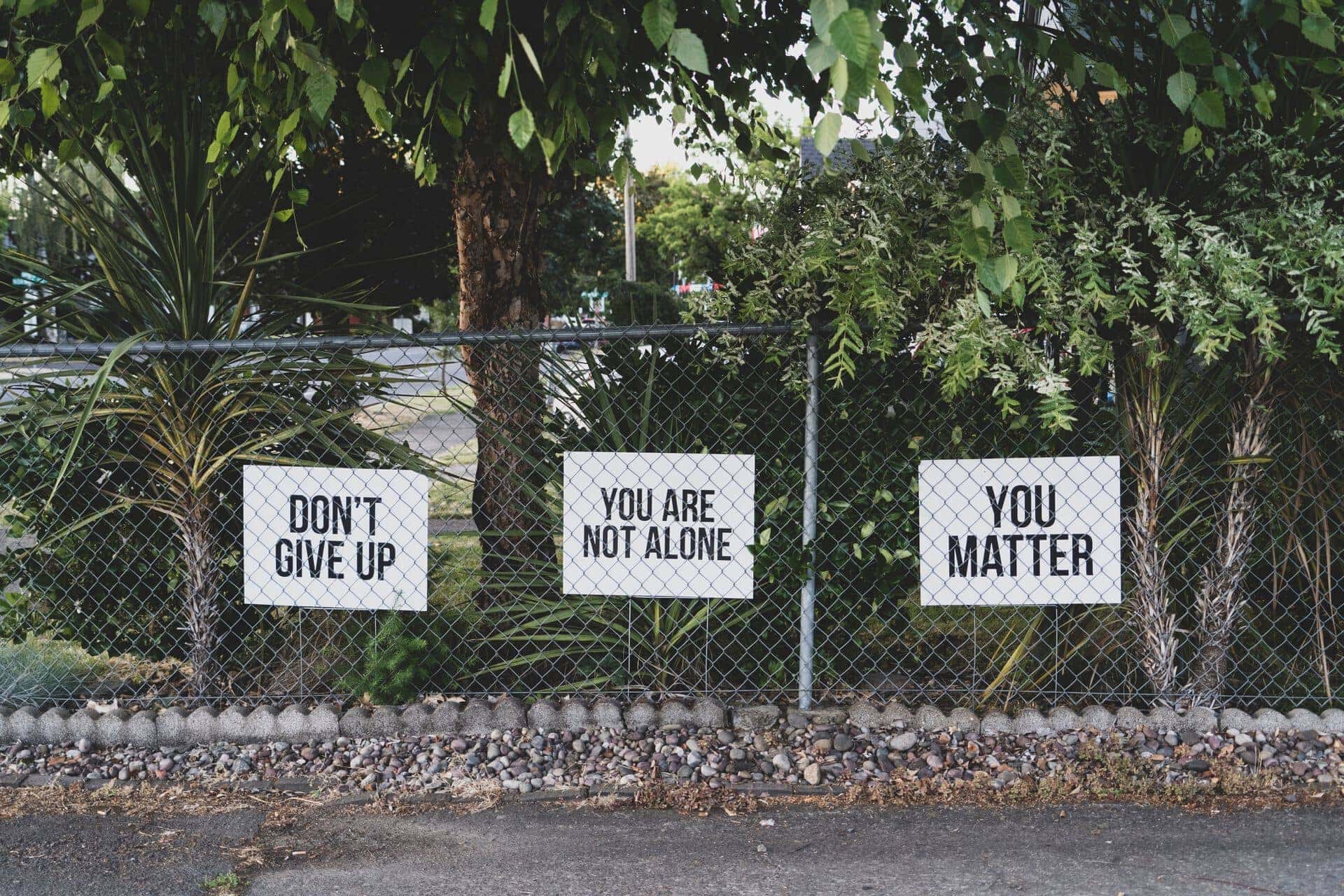

Editor’s note: This column contains references to suicide and suicide prevention. If you’re feeling suicidal, call West Virginia’s free crisis hotline to find local help with issues surrounding mental illness and addiction at 1-844-HELP-4-WV (1-888-435-7498) or the national Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

September is National Suicide Prevention Month, this week is National Suicide Prevention Week, and Tuesday, Sept. 10, was World Suicide Prevention Day.

And I’m going to try to talk about it.

But how do you write about suicide prevention, especially when you live in a small town where you can’t hide behind the mask of anonymity and the subject still seems taboo, regardless of the fact that it happens repeatedly and that there are numerous other close calls?

One of my favorite pieces of advice about writing is, perhaps tragically and fittingly, a quote by American journalist, novelist and short story writer, Ernest Hemingway, who wrote, “Write hard and clear about what hurts.”

In essence, don’t try to dress up your prose with a lot of fluff or flowery words; get to the point and write about what hurts, what’s poignant, what matters in this life.

It hit me a second later that Hemingway, author of “Farewell to Arms,” “The Old Man and the Sea” and other classic pieces of American literature took his own life July 2, 1961.

It seems self-evident to say suicide “hurts” so many people in so many ways, the most obvious being the crippling mental and emotional pain at the root of chronic suicidal thoughts, as well as the pain deaths by suicide cause the family, friends, co-workers, children, community members, and yes, even pets, of those left behind.

Death by suicide is now the 10th leading cause of death among Americans across all age spectrums, and, most alarmingly, the second leading cause of death among people in the U.S. ages 10-34.

That. Is. Terrifying.

We can no longer afford to not talk about it, especially in rural areas, where, according to findings by a WVU researcher, people living in rural areas facing poverty are more likely to take their own lives than people who might lack resources in more metropolitan areas. The study, which focused on people ages 25 to 64 living in rural areas from 1999 through 2016, also found suicide rates are rising the fastest in rural counties.

Rural counties like Upshur, Lewis, Randolph and Barbour.

During weeks like this, when mental health is at the forefront of national conversation, writers and mental health advocates point to these statistics, and an abundance of articles direct struggling people to the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline – 1-800-273-TALK or 1-800-273-8255.

That’s great.

This week is a short blip of time during which it feels OK to talk about suicide, and many mental health organizations encourage suicide attempt survivors or those impacted by suicide the chance to share their stories.

That’s also great. As is the case with substance abuse and addiction, I believe the more we collectively understand how widespread mental illness is – severe mental illness that can lead to suicide – the less likely we are to stigmatize it.

That’s because we understand it as a shared problem, a shared condition to which any human being is vulnerable.

This is evident today in how many more people appear to feel comfortable sharing their struggles with major depressive disorder or general anxiety disorder. We’re almost to the point where talking about depression and anxiety is like talking about a common cold – the type of cold that affects your emotional and psychological wellness.

At the same time, I know sharing carries with it a great deal of risk.

Even though many readers and listeners absorb people’s stories with understanding, compassion and self-recognition, people still judge others based on their stories. Judging is a natural tendency; it’s how the brain makes sense of situations and is able to quickly file events and concepts into categories.

As a recovering over-sharer, I subscribe to the philosophy of vulnerability and shame researcher Brene Brown, who holds that only when you have worked through something painful do you have the wherewithal to share it while standing on solid ground.

Personally, I believe only people who know you well and have earned your trust should hear the most intimate details of your journey.

So, suffice it to say I have been on a journey, and what I do want to share are some ideas and strategies I’ve found useful in my own healing process or have learned about from other people.

Please understand I’m offering these ideas as additions to, and not as a replacement for, counseling, psychotherapy, medication and other forms of treatment.

Find a ‘trusted person’

It’s crucial to have at least one person – even if it’s a therapist – with whom you can be completely honest, who you don’t feel judged by and who has some familiarity with your history as a human being on this earth. This person can listen to you without always feeling obligated to fix things, and she or he can also hold you accountable when you’re trying to accomplish small goals on your way to getting well.

If needed, this person can serve as a contract-for-life person, meaning you and your trusted person write a sign a contract in which you promise not to harm yourself.

Limit your time on social media

When we’re depressed, we’re especially vulnerability to fall into a damaging habit of comparing our worst days to the doctored images of other people’s best days. One helpful action you can take is unfollow or “mute” accounts that aren’t good for your mental health and follow ones that focus on things you love; on hobbies you want to hone; on self-care; or that nurture your spirit in some other fashion.

Comparison is one reason I think social media can be harmful, but another, more insidious one is that we – and not just middle-schoolers or teenagers but full-grown adults – lean on it too heavily as a form on external validation.

So when I catch myself spending too much time on my phone or see young adults spending too much time on their devices, my thought isn’t, “she or he is too absorbed in social media and technology to care about the world around her or him.”

Instead, my worry is, he or she is learning to rely on an external form of validation that is not only elusive (because it’s the internet) but highly unreliable, and therefore capable of triggering some wild emotional rollercoaster rides.

Make up a mantra

One of the most wonderful things about the human brain is its neuroplasticity or ability to learn, change and “rewire” itself throughout the span of your life. That’s how people recover the ability to move or speak or walk following traumatic brain injuries. (There are tons of books on this subject, and one is Rick Hanson’s “Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm and Confidence.”)

That’s also how people recover from psychological trauma, depression, anxiety and other conditions. Make up a mantra that affirms your self-worth and your innate value and dignity as a human being. Or maybe a prayer works better for you. Whatever it is, whether you currently believe the words or not, repeat it often enough and you will most likely come to believe it over time.

Read, read, read

One of the hardest pills to swallow when coping with mental illness is this: there’s no magic cure or fix-all pill. You have to be your own advocate at a time when you probably don’t feel like it. Reading self-help or spiritual books is something you can do to help yourself heal. These books don’t need to be about mental illness; they can be about strengthening your faith in God or exploring your spirituality, and they can outline coping techniques. Take from these resources what resonates the most with you and leave the rest.

I’ll mention several I’ve read or have heard are helpful: “Radical Acceptance: Awakening the Love That Heals Fear and Shame” by Tara Brach; “The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion: Freeing Yourself From Destructive Thoughts and Emotions” by Christopher Germer; “Life of the Beloved: Spiritual Living in a Secular World” by Henri Nouwen; and “Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness” by Jon Kabat-Zinn. Kabat-Zinn also wrote “The Mindful Way Through Depression: Freeing Yourself from Chronic Unhappiness” with several other authors.

Virtual and real-life hope boxes

If you’re having trouble feeling compassion for yourself, I highly recommend digging up old pictures of yourself as a small child and trying to have compassion for that child. This advice from meditation teacher Jack Kornfield sums up how useful this practice can be: “You were once a young child, just as worthy of care as any other,” he writes. “The same is true today: You are a human being like any other – and just as deserving of happiness, love and wisdom.”

Assemble collections of pictures of people and animals, quotes, reminders or miscellaneous sources of hope in a box or container. Luckily, there are also apps for that, and two good ones are Virtual Hope Box and Stay Alive.

Consider questions surrounding self-worth

Often at the root of people’s depressive and/or suicidal thoughts is the belief that they are not worthy human beings or that they are an innately “bad” and must continually strive to earn worth. My dad taught me it’s important not to confuse the concepts of “self-esteem” and self-worth.

While self-esteem – defined as the way you feel about yourself in any given moment – can rapidly change depending on a whole variety of circumstances, having self-worth is holding the fundamental belief that you are a worthy human who deserves love and respect just because you are alive.

“The most important thing to know about worthiness is that it doesn’t have prerequisites,” Brene Brown writes in her book, “Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead.”

Shame – probably the most destructive of human emotions – has to do with feeling bad about who you are at your core; as Brown writes, “Shame loves prerequisites.”

In the beginning of the first chapter of her book, “Real Love: The Art of Mindful Connection” well-known mindfulness and meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg sums this up nicely.

“You are a person worthy of love,” she writes. “You don’t have to do anything to prove that. You don’t have to climb Mt. Everest, write a catchy tune that goes viral on YouTube, or be the CEO of a tech start-up who cooks every meal from scratch using ingredients plucked from your organic garden … You do not have to earn love. You simply have to exist.”

It’s true.