Only about half of West Virginians who graduate high school enroll in college. What if there were a way to boost that number to nine in 10?

The West Virginia Health Science and Technology Academy is one avenue that has proven highly effective over its 25 years of operation. The mentorship program reaches out to high school students from backgrounds underrepresented in college—across the state—and encourages them to pursue STEM and health science degrees.

After completing the program, 99 percent of HSTA participants go to college. Of those, 87 percent complete a four-year degree, and 61 percent major in a health science or STEM field.

“We started with 44 kids and nine teachers in two counties. One of them was McDowell, and the other one was Kanawha County—a rural and an urban county,” said Ann Chester, the assistant vice president of education partnerships for West Virginia University’s Health Sciences Center, who founded and directs HSTA. “We figured if we could make it work in the most urban and most rural counties in West Virginia, maybe we could make it work in more counties.”

This year about 750 students, in 26 counties, participated.

“HSTA got started because there were not enough doctors, dentists, pharmacists, nurses or other healthcare professionals in most of West Virginia. We needed to grow our own,” she said.

From calipers to cadavers: a diversity of experiences

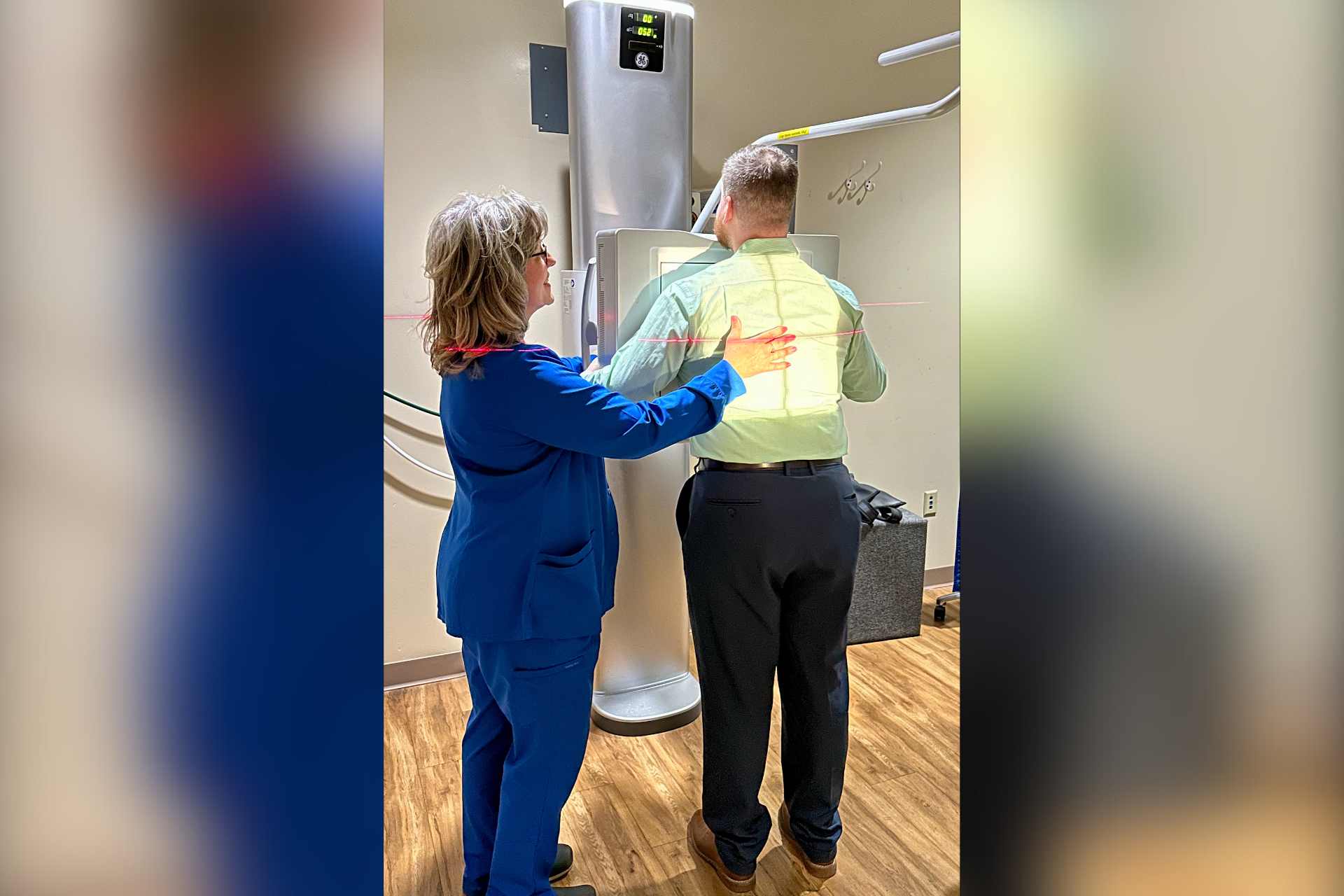

High school teachers, community members and higher education faculty, staff and students host HSTA participants during summer camps at five colleges and universities: WVU, WVU Potomac State College, Marshall University, West Virginia State University and Glenville State College. The camps are free and transportation is provided.

Camp activities vary year to year among locations. For instance, students may engage in simple experiments such as using calipers to measure body fat, or visit a cadaver lab to observe how obesity, black lung disease and cancer affect human organs. During that time, a HSTA participant may also investigate how therapy animals help nursing home residents, develop an antibullying curriculum for high school and work with preschoolers to encourage them to stay active and eat healthy snacks.

One WVU staff member who worked with HSTA participants was Renée Nicholson, the interim director of WVU’s multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary studies programs. She collaborated with palliative care physicians at the WVU Cancer Institute to capture the life stories of patients receiving chemotherapy.

“Because so many HSTA participants are interested in medical school, I developed a lecture and workshop to introduce them to narrative medicine,” Nicholson said. “I shared with them the work we were doing in the Cancer Institute, and then we wrote from the prompts I used with patients. Students were able to share their writing, or keep it private, and we discussed how knowing a patient’s story could help a clinician better serve their patients.”

The stories they wrote helped the palliative care physicians write more meaningful advance directives for their patients. They also helped occupational therapists plan more personalized treatments.

“During our session, many students had never heard of narrative medicine or the broader medical humanities, so it was a really good opportunity to show how STEM and other fields could be interrelated in meaningful ways,” Nicholson said.

Even though the summer-camp activities and their community-based counterparts cover a wide range of topics and skills, they have a common goal: fostering a passion for STEM and health sciences in young people who—as a group—tend not to pursue those fields.

HSTA participants are predominantly young women who come from rural areas and are the first in their families to attend college. And even though just 4 percent of West Virginians are African-American, 37 percent of HSTA participants are.

“We have kids with tremendous potential and tremendous energy across the state, regardless of their backgrounds or their race or ethnicity,” Chester said. “But what we don’t have is opportunity. HSTA is trying to increase the reach of opportunity into the populations where the students are not likely to succeed without us. If we can reach into those populations and cultivate those kids to be successful in careers where we desperately need them, they’re more likely to go back into West Virginia and to their populations and to make a difference.”

In addition, nearly half of HSTA participants are economically disadvantaged. By the time they complete a four-year degree and accept their first job after graduation, they earn—on average—$30,000 more than their parents’ highest salaries.

The support HSTA provides isn’t purely in the form of mentorship. It’s also financial: HSTA participants who complete the program are offered tuition and fee waivers to attend West Virginia state colleges and universities.

‘I found out I could be a researcher’

The waivers can give HSTA participants confidence that they can complete their college degrees and won’t have to drop out because it costs too much.

“I knew I had the tuition waiver, so I knew I would graduate,” said Mya Vannoy, who participated in HSTA from 2012 to 2016. “It gave me a pathway to follow.”

Vannoy is now an undergraduate at WVU majoring in immunology and medical microbiology. She deems the summer camps the highlight of her HSTA experience.

“I had never been on a college campus. I’d only seen them on television. I feel like putting kids on college campuses makes it real for them. It made it real for me. I realized I could go to school. It was a real place that I could actually go to, not some distant dream that wasn’t plausible for me,” she said.

She had always been interested in science. She’d read about it. She’d watched TV shows about it.

“[But] HSTA told me I could have a career in it,” she said. “I found out I could be a researcher and do experiments all day, and that could be my job. And that is what I really want to do.”

Stephanie Tyree attended HSTA when the program was still new. She participated in it for the first time in 1996 and completed it in 2000. Today, Tyree holds her juris doctorate and is the executive director of the West Virginia Community Development Hub.

“Before HSTA, I’d never had the experience of strangers inviting me to stay with them, welcoming me with open arms,” Tyree said. “But I literally spent weeks with my friends’ families, getting to know communities that weren’t on my radar at all and were different than my own in big and little ways. It gave me both a self-awareness and an awareness of the world around me. That’s at the root of community development. There is uniqueness in each community, but we’re all trying to do similar work to make our communities better.”

Since the program’s inception, more than 2,000 students like Vannoy and Tyree have completed it. That number is larger than the total populations of some participants’ hometowns. For example, just 1,700 people live in the county seat of McDowell County, one of the two counties where HSTA got its start.

Staying power

How could HSTA afford to assist so many students over more than two decades?

Legislative buy-in and community support.

“What we are is a community/campus partnership with multiple campuses and community leadership from around the state,” Chester said. “Those community members immediately started making a difference. They’re the ones who knew which students needed HSTA the most. They’re the ones who were able to get the legislature to pass the tuition waiver back in 1997.”

She also attributes HSTA’s success securing additional funding sources—including from the National Institutes of Health and the Claude W. Benedum Foundation—to community involvement.

Chester envisions HSTA persevering—and growing—over the next 25 years.

“I would love to see HSTA as a national model. I would like to see it as frequently talked about as the Scouts or 4-H or Boys & Girls clubs. It would be really great if those entities could take on HSTA as a subset of their organizations and make opportunities much more widely spread for all populations.”