By Allen Siegler, Mountain State Spotlight

Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Mountain State Spotlight. Get stories like this delivered to your email inbox once a week; sign up for the free newsletter at https://mountainstatespotlight.org/newsletter

Last month, the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources had rare good news to report: The number of West Virginians dying of drug overdoses each year was slowing, according to new data.

“West Virginia Overdose Deaths Showing Improvement,” DHHR touted in a press release. But Joe Solomon was unimpressed.

It wasn’t that the news, a 4% decrease in the state’s overdose deaths compared to the previous year, was unwelcome. Rather, the co-director of Charleston-based harm reduction nonprofit SOAR was concerned that the number — 1,487 West Virginians killed by drugs — was still astronomically high, even compared to a few years ago.

“You ever have a friend get sick and you ask them how they’re feeling and they say ‘Well, I don’t know, 3 to 4 percent better?’” said Solomon.

In recent years, DHHR has made efforts to expand the use of some medications, like naloxone, that are known to keep people with substance use disorder from dying due to overdose.

At the same time, state lawmakers have passed and maintained policies that restrict West Virginians’ ability to access other proven tools, most notably methadone clinics and clean needle exchange sites.

Without full use of these strategies, addiction experts are concerned that the state’s residents will continue to die at rates higher than anywhere else in the country.

“We have politicians dictating health care policy right now,” said Connie Priddy, a Cabell County EMS nurse who leads the Huntington harm reduction initiative Quick Response Team. “So even though science tells us best practice is to do X, Y and Z, many of our politicians are not doing that.”

Unprecedented numbers

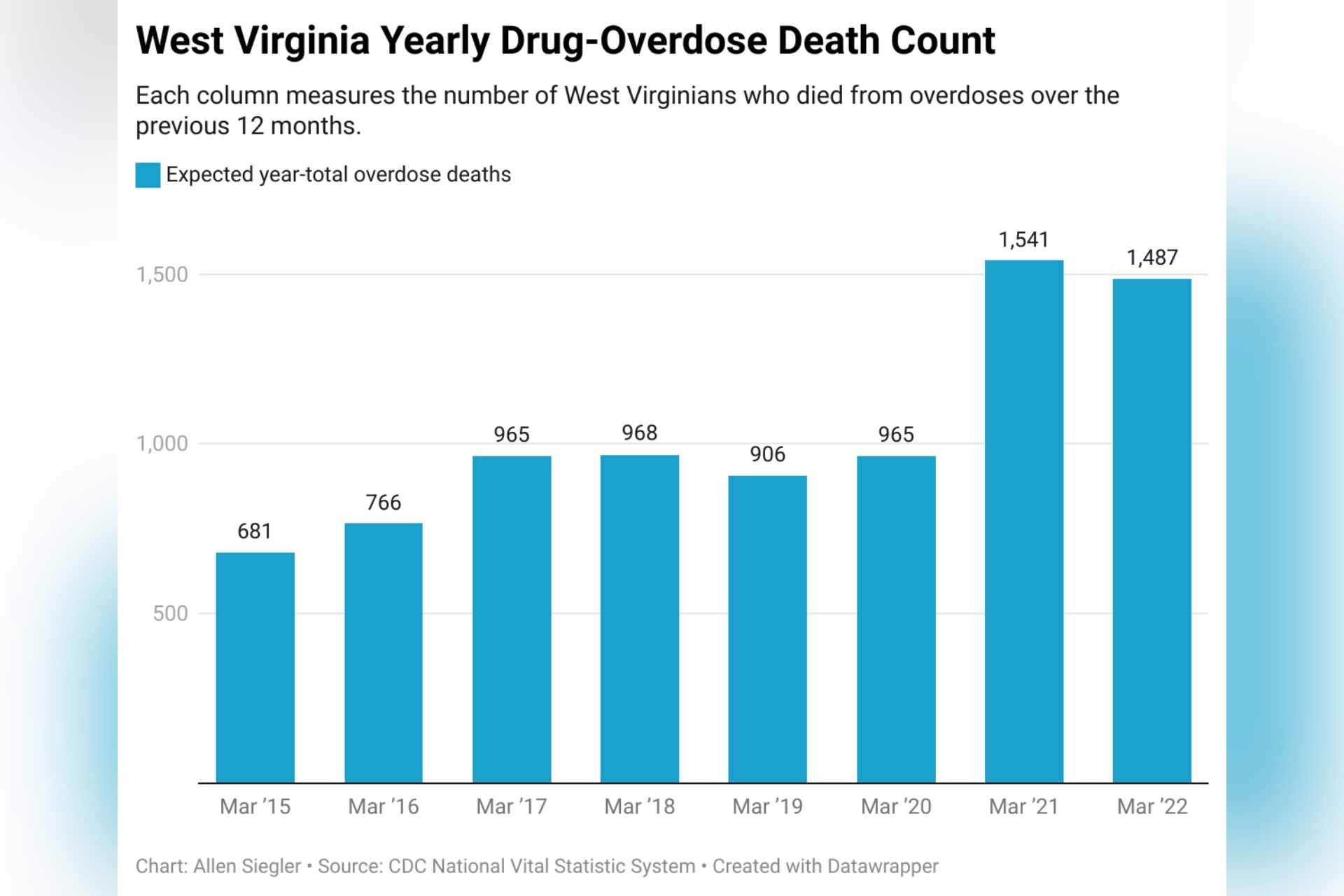

Each month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks the number of drug-related deaths over the past year. While the West Virginia count has decreased slightly since 2021, the number of deaths over the last three years has been unprecedented.

In 2016, when U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy labeled the opioid epidemic as one of the country’s most urgent health problems, West Virginia led the country in per-capita drug overdose deaths. That year, 892 people in the state died from drugs. Over the next three years, deaths fluctuated some but remained near or under 1,000.

Then, in 2020, the body count ballooned. By the end of that year, the CDC estimated 1,330 West Virginians had died as a result of drug overdoses. The figure continued to grow in 2021 to more than 1,500 and has only returned under that threshold recently.

When comparing March 2016 to March 2022, nearly twice as many people are dying from overdoses every year.

“Looking at CDC data, we lost over four lives a day in 2021,” Solomon said. “It’s not much better in 2022.”

Dr. Matthew Christiansen, DHHR’s Office of Drug Control Policy director, attributed the increased death count in recent years to the rise of illicit fentanyl, an opiate vastly more potent than heroin.

“Fentanyl has made the problem worse. There’s no doubt about that,” he said.

In response, Christiansen said, his office has ramped up efforts to combat addiction and prevent overdoses.

“We continue to double down on the things that we know work … evidence-based programs, naloxone, access to medication recovery resources, prevention and harm reduction programs that link people to treatment,” he said.

But even as the problem worsens in West Virginia, the tools in DHHR’s toolbox have become fewer as state lawmakers have limited the use of some proven techniques to combat the crisis.

Methadone, a medication replacement therapy, is one of the most studied and established treatments for reducing opioid dependency. Scientists have repeatedly proven that the medicine reduces detox symptoms, enables people with opioid-use disorder to maintain functional lives and reduces the risk of transmission of diseases like AIDS and hepatitis.

But since 2007, state law has blocked any new clinics that offer methadone. Nine clinics, seven of which are operated by the same for-profit health care company, still offer methadone services in West Virginia, but new clinics cannot be built.

Earlier this year, Delegates Buck Jennings, R-Preston, and Matthew Rohrbach, R-Cabell, sponsored House Bill 4607 with provisions that would have removed the ban; the bill passed the House but died in the Senate on the final day of the session. Christiansen said that despite the moratorium, DHHR has focused on expanding buprenorphine, another well-established method for reducing overdose risk; some research indicates it is less effective than methadone at keeping people in treatment.

“Methadone is an evidence-based medicine,” he said. “We know that it works to reduce illicit drug use, and it’s something we need to work more on getting access to.”

A newer hurdle for people on the front lines of West Virginia’s overdose crisis is Senate Bill 334. The bill, passed by lawmakers and signed into law by Gov. Jim Justice in April 2021, puts new restrictions on clinics around the state who let people with substance use disorder access clean, sterile needles.

Priddy, the Cabell EMS nurse, said adding restrictions to safe needle exchanges leads to more drug overdoses. She says though it’s often overlooked, these programs can be the first place people with substance use disorders seek rehabilitation resources.

“They’re talking about recovery, they’re talking about treatment, they’re not just needle exchange services,” Priddy said. “These individuals are getting lots of services when they take it upon themselves to go somewhere to utilize services for syringe exchange.”

Since the bill passed, multiple needle exchange programs across the state have been forced to shut down.

Considering broad factors

Sometimes, conversations about how to prevent West Virginia overdoses frustrate Kelli Caseman. Caseman, the executive director of Charleston-based nonprofit Think Kids WV, has heard, read about and been part of many opioid discussions that focus only on the moment when someone is at a crisis point.

Caseman recognizes the importance of providing as much effective treatment as possible. But she also wants legislators to consider other factors that drive addiction.

“We have to look at it also in the context of social determinants of health,” Caseman said.

She believes preventing and addressing adverse childhood experiences is one way to decrease future overdoses. Traumatic experiences, such as watching a parent overdose, are known to be predictive of future drug use if unaddressed.

If policymakers created stronger safety nets for West Virginia children, one that ensured mental health services for youth who need them, Caseman is confident it would reduce overdoses in the future.

“All of that comes back to what kind of resources and community support we have at the community level for families,” she said.

Solomon, Christiansen and Priddy all agree that creating an environment in which West Virginians are at lower risk for developing substance use disorders is essential for lowering the number of overdose deaths. Christiansen noted that addressing adverse childhood experiences and offering more mental health services are priorities in the West Virginia 2020-2022 Substance Use Response Plan. But the plan was written in 2020, and a spokeswoman didn’t return a request for comment about what progress, if any, the state had made on those issues.

Solomon has found that confronting deeper societal problems will also be essential for curbing overdose deaths in the state. To end the collective pain of the state’s opioid crisis, he thinks changing what policymakers consider to be health legislation will be necessary.

“We are not talking about how a living wage is an overdose zero wage,” he said. “How investing in our schools and our teachers is also overdose prevention, or how challenging systemic racism is also overdose prevention.”

Reach reporter Allen Siegler at allensiegler@mountainstatespotlight.org.