BUCKHANNON, W.Va. — The West Virginia Wesleyan College Art Department will feature artist, activist and environmentalist, John Sabraw on Jan. 17 at the Sleeth Gallery in McCuskey Hall. The opening reception will be held from 4:30 to 6 p.m., and will be followed by an artist lecture at 6 p.m. The reception and lecture are open to the general public.

Sabraw’s paintings, drawings, and collaborative installations are produced in an eco-conscious manner, and he continually works toward a fully sustainable practice. He collaborates with scientists on many projects, and one of his current collaborations involves creating paint and paintings from iron oxide extracted in the process of remediating polluted streams.

Sabraw’s art is in numerous collections including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Honolulu, the Elmhurst Museum in Illinois, Emprise Bank, and Accenture Corp. He is represented in Chicago by Thomas McCormick.

Sabraw, a native of Lakenheath, England, is a professor of art at Ohio University where he is chair of the painting and drawing program and board advisor at Scribble Art Workshop in New York. He has been most recently featured in TED, Smithsonian, New Scientist, and Great Big Story.

—About the Exhibition—

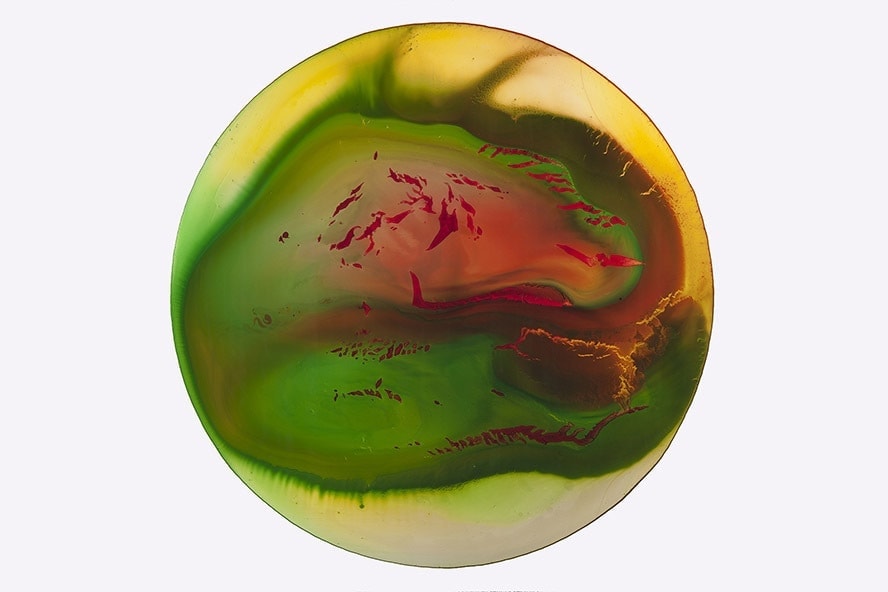

Exhibition Title: Apposite

Art Statement: These colorful and highly textured paintings celebrate connectivity to nature by examining chroma and structure in micro-macro relationships. These works of art utilize pigments generated by remediating streams polluted with coalmine runoff called acid mine drainage.

We observe natural systems in action and see that they are irregular; their structures form under the influence of natural law without conscious ideas of what they will become. Systems like these occur at macro and micro levels in nature and it is we as humans who seek understanding; the laws of physics that determine the flow of great river deltas also affect the patterns we observe in leaves and tree bark, and even water with some added pigments can flow and set into beautiful imagery reflective of these natural phenomena. The result is complex, luminous, mysterious paintings that strike a beautiful balance between controlled and organic processes.

Art Bio: Artist John Sabraw was born in Lakenheath, England. An activist and environmentalist, Sabraw’s paintings, drawings and collaborative installations are produced in an eco conscious manner, and he continually works toward a fully sustainable practice. He collaborates with scientists on many projects, and one of his current collaborations involves creating paint and paintings from iron oxide extracted in the process of remediating polluted streams.

Sabraw’s art is in numerous collections including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Honolulu, the Elmhurst Museum in Illinois, Emprise Bank, and Accenture Corp. Sabraw is represented in Chicago by Thomas McCormick and Martha’s Vineyard by Sargent Gallery.

Sabraw is a Professor of Art at Ohio University where he chairs the Painting + Drawing program, and Board Advisor at Scribble Art Workshop in New York. He has most recently been featured in TED, Smithsonian, New Scientist, London, and Great big Stories.

Toxic Art Project: These abstract explorations focus on natural phenomena, the earth’s ecosystem as a whole, and our role within that. This understanding has led me to incorporate ever more sustainable practices in my studio, in my life, and when possible actively engaging the public on the matter.

In this body of work, pigment manufacturers and types are chosen with permanency and sustainability in mind. This goal is more attainable now since I have been partnering with Ohio University engineer Dr. Guy Riefler to develop paints with pigments derived from toxic runoff from abandoned coal mines – acid mine drainage or AMD for short.

In Southeastern Ohio many of the streams run orange. Throughout the first half of the 20th century strip mining and room-and-pillar mining were common throughout this region. Forests were clear cut, soils scraped away, and tunnels dug to remove the coal. A few active coal mines continue in the region, but by the 1970s most of the mining companies had moved on leaving behind open mines and disturbed land, with inadequate restoration.

Much of the forest has now regrown, although it is young, but the underground mines continue to release toxic water to streams. When abandoned, many of the mines fill with water, and the oxygen and water react with mineral surfaces that had been buried for 300 million years. When sulfides are present, these are common in Appalachian coal deposits, very high concentrations of sulfuric acid and iron are produced. In one local seep, over one million gallons per day of polluted water enters Sunday Creek. This water has a final pH below 2 and over 2000 lb of iron per day. It is like junking a car in the stream every day. However, Engineer Professor Guy Reifler started asking what if the iron sludge could be sold as a valuable resource rather than disposed of as a waste product? What if treating pollution could be an entrepreneurial endeavor rather than a societal cost?

Artist and Professor John Sabraw was able to the turn our powdered iron minerals into a working paint for the first time. Recently Professor Sabraw has developed a relationship with a large paint company that has agreed to produce a batch of 500 37ml tubes of oil paint using our pigment. These paints are being distributed to artists around the world through a Kickstarter Campaign and the resulting artworks curated into a touring exhibition highlighting our efforts and generating broader discourse on developing more sustainable art practices.

With little funding and lots of skeptics, we are starting to refine a process that can continuously treat AMD, restore a stream for aquatic life, and collect iron pigment that can be sold offsetting operational costs. Based on our best estimates, we should be able to create a few jobs and produce a small profit, while eliminating a perpetual pollution source. We are currently wokring with a pilot facility at a Corning, Ohio field site after securing funding from the Sugar Bush Foundation to demonstrate the process and begin producing large quantities of pigment. Hopefully, in another 10 years we will have started a new industry in Southeast Ohio that turns pollution into paint while restoring our watersheds.