MINGO COUNTY — Jamie Cantrell was lucky: For 20 years, she was one of a dwindling number of Mingo County natives to hold onto a solid job in the coal industry. But in 2020, she was laid off from her job selling raw coal.

“I was devastated,” Cantrell said. “So I said to my husband, ‘Let’s do something with the trail system.’”

Cantrell had watched as tourism brought more and more money into Mingo County, driven largely by the opening of the Hatfield-McCoy ATV trails. Like many residents who had stuck around as the coal industry’s decline took its toll on their communities and neighbors, she thought the shift toward tourism offered hope that the town where she grew up could bounce back.

Since Cantrell also worked managing a nearby campsite, she knew there was an appetite for a place to get a drink and some hearty food. So she and her husband bought and renovated a space in downtown Matewan. In March, the Trailhead Bar and Grill opened. And so far, business has been good.

Mingo County is undergoing a slow transformation. Once it was the heart of a thriving coal industry that offered middle class jobs and supported local businesses, but the industry’s decline led to decades of steep economic and population losses. Now, residents and officials are pinning their hope on tourism, though wary of creating another single-industry economy.

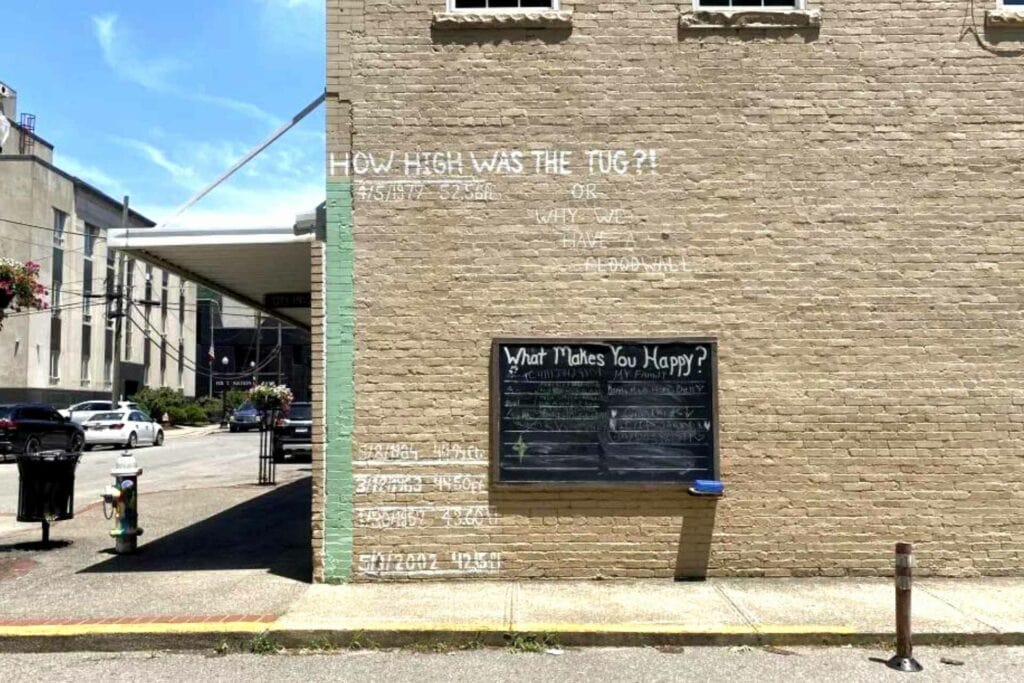

Longtime Mingo County residents can point to specific moments, like marks on a graph, to illustrate the decline of their town’s economy. There was the flood of 1977 that saw parts of the county seat, Williamson, drown in over 50 feet of water, killing 22 people and destroying many homes and businesses in the greater Tug Valley area.

In 1984, Williamson flooded again, though not as severely. That led to a small exodus.

In the early 1990s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built floodwalls around Williamson and Matewan. While those likely staved off further disasters, residents also say the floodwalls directed traffic around the cities, especially Matewan, putting further strain on an economy that was already crumbling from the loss of coal jobs.

In 2011, high schools closed in Delbarton, Gilbert, Matewan and Williamson, and students were sent to a consolidated high school.

Throughout it all, coal production and coal jobs dissipated. The severance taxes paid by coal companies shrunk too, hamstringing hopes of local government-funded revival. Now, the county’s population is about half what it was in 1950.

Jim Pajarillo, 49, is a criminal defense lawyer in Williamson. On a bench behind his office recently, he chain-smoked American Spirit cigarettes and recalled what the old Williamson High School meant to his childhood, and to the community at large.

Many who went there look back at the school with pride, remembering the football team or marching band. It was also, once, relatively diverse. Pajarillo was one of a number of students from Asian immigrant families, and he said he never felt out of place. At its peak, the area also had a relatively sizable Jewish population, but the only synagogue closed in 2009.

The school was also a revenue source for Williamson businesses. At the end of the school day, kids would flood into local stores and restaurants.

Now, the high school is roughly a 30-minute drive from the center of town. Kids who take the bus wake up early and get home late.

“We know what we had when we were young,” Pajarillo said. “Now we have even less.”

Since he moved back to Williamson after a young adulthood spent in California, Pajarillo has dedicated himself to reviving some of the opportunities awarded to him by the town where he grew up. Aside from his work as a lawyer, Pajarillo sits on the board of the Tamarack Foundation for the Arts, a West Virginia nonprofit dedicated to fostering local art.

He’s begun an open mic event, started art classes for kids and launched a local comics convention called WillCon, which attracted nearly 3,000 people before the pandemic.

Tourism, he hopes, will build a bigger audience for some of these events and bring money into the local arts scene. Pajarillo wants to use that platform to reframe Williamson’s narrative, which has been so defined by the decline of coal and the opioid crisis.

“There are no pie charts that show what an art class or a music class benefits the community, but you just kind of have to take a leap of faith,” he said.

Around Williamson, signs of revival are budding. Whether it’s the opening of several new restaurants, the restoration of the historic Mountaineer Hotel, or just the sound of four wheelers on the streets — a sign of tourists using the Hatfield-McCoy trails.

Like the coal industry put money in people’s pockets to spend at local stores, tourism is bringing customers and spreading the wealth to those who can afford to invest. And while wary, residents hope they’re beginning to chart the reverse of the economic collapse of the last several decades.

Some point to the opening of the Hatfield-McCoy trails in 2000 as the beginning of a turnaround. More recently, the pandemic brought more tourists interested in the kind of nature-focused vacations that the area offers.

Still, the trail system has yet to bring in the number of visitors that early supporters promised, and other businesses that can hold tourists’ attention have been slow to develop.

Williamson Mayor Charles Hatfield says that economic diversification is key to the town’s future.

“We gotta shake the bonds of being dependent on one industry,” he said. But there are significant obstacles: the area’s topography isn’t ideal for the kind of infrastructure that can attract industry, broadband and cell service issues persist, and residents are older and fewer.

“I’m not a fool,” Hatfield said. “Tourism will not replace the good-paying jobs of mining coal, and the railroad industry, which was an ancillary part.”

However, he hopes that tourism will bolster other local businesses, and force new business owners to get serious about things like beautification and making the area more attractive to young people and families.

Crystal Little, 35, is the kind of local business owner who Hatfield hopes will benefit from a bigger tourist economy.

When she was a kid in Delbarton, Little was allergic to cats and dogs, so her grandparents got her a gecko. That was the beginning of her fascination with exotic pets.

For years, Little bred them — mostly reptiles — and sold them to enthusiasts over the internet and at exotic pet shows.

In March 2021, Little opened a pet store in Williamson, Sky High Geckos. It was hard to get any buy-in for an unproven business in a struggling town.

“I was honestly laughed at by a lot of male store owners around here,” Little said.

But Little ultimately found support from a landlord excited about what the business could bring to the culture of Williamson. He worked with her to keep her deposit affordable. Now, the local chamber of commerce and the mayor speak highly of Little.

“I never thought the local politicians would support the crazy gecko lady,” Little said. “But here we are.”

Little mostly sells pet supplies. But on an afternoon in June, a family considered which of a pen of rabbits they might adopt, and Little showed her newest pets to another regular who was just there to look.

But empty storefronts surround her store. Years ago, there were two operating theaters within blocks. Now, both are closed.

Mingo County residents who want to start businesses and help revitalize the area face high costs to invest. Outside investors can buy up property to run bed and breakfasts, or just hold onto vacation homes.

According to Leigh Ann Ray, grant coordinator with the Mingo County Commission, county residents are at a disadvantage. Many don’t have much money, or have bad credit, or are just plain wary of investing after decades of decline. For years, residents say, it was taken as a truism that, to find opportunity, residents had to leave Mingo County.

Ray, who grew up just over the Tug Fork River in Kentucky, doesn’t see an issue with outside investment.

“Money is money and investment is investment,” Ray said. “If someone is investing in your area, what does it matter, geography?”

But not everyone agrees.

Dave Wesley Hatfield, 63, runs an Airbnb as well as Appalachian Lost and Found, a souvenir store in Matewan that also doubles as something of a general store. After 30 years as a locomotive engineer, Hatfield decided to remain in his hometown and invest in the growing tourist economy, which he felt was something of a duty.

Working on the railroad, Hatfield said, “I saw entire neighborhoods, businesses, just disappear over 30 years. Just total decimation… I didn’t want to see that happen here.”

While the prospect of tourism has given him an opportunity to grow a business in his hometown, something that he isn’t sure would have been possible 10 years ago, he’s not convinced that the industry will solve the area’s economic problems.

“[We] have a lot of people from outside the area who are investing here,” he said. “So you’re creating the same thing you had before. It’s extraction.”

But for Wilson Chafin, 74, who lives at the end of the same block as Hatfield’s store, some things about the area will never change. He sits on a bench outside his home and across the street from the Mine Wars Museum that commemorates the area’s bloody labor struggles in the early 20th century.

Despite the ebbs and flows of the economy since his childhood — and decades of his adult life spent away from West Virginia — Matewan is home and Chafin doesn’t think about leaving.

“I left home when I was 18, came back when I was grown, but it’s the same old mountains,” he said. “I never get tired of looking at the mountains.”

Chafin doesn’t think that the coal and oil industries are coming back. He blames environmental regulations and regulatory red tape.

But he hopes that the mountains can be repurposed by future generations, and once again become the lifeblood of his hometown.

“It’s hard to visualize what it would look like,” he said. “But I’m real optimistic.”

Reach reporter Ian Karbal at iankarbal@mountainstatespotlight.org.