Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Mountain State Spotlight. Get stories like this delivered to your email inbox once a week; sign up for the free newsletter at mountainstatespotlight.org/newsletter

By Erin Beck, Mountain State Spotlight

Along a Parkersburg river bank, Stephanie McCumbers keeps watch from her tent for people who might hurt her or steal her belongings.

This means she has to stay vigilant during the day, and she said she can’t sleep at night because of night terrors caused by post-traumatic stress disorder. As her puppy Baby nuzzles her face and neck, she said the dog does provide her some comfort.

While her husband works two jobs, she calls local shelters almost every day, but she’s always told there’s no room.

“And then we get in trouble for being out here,” she said.

As winter approaches, Parkersburg and Wheeling, two of West Virginia’s largest cities, are taking stricter measures towards people experiencing homelessness.

City officials want to ban people from sleeping in public spaces like parks and sidewalks and direct them to shelters instead.

In both cities, there are not enough open shelter beds for everyone who is sleeping outside, according to shelter directors and staff. Shelters also have rules that bar some people from accessing them.

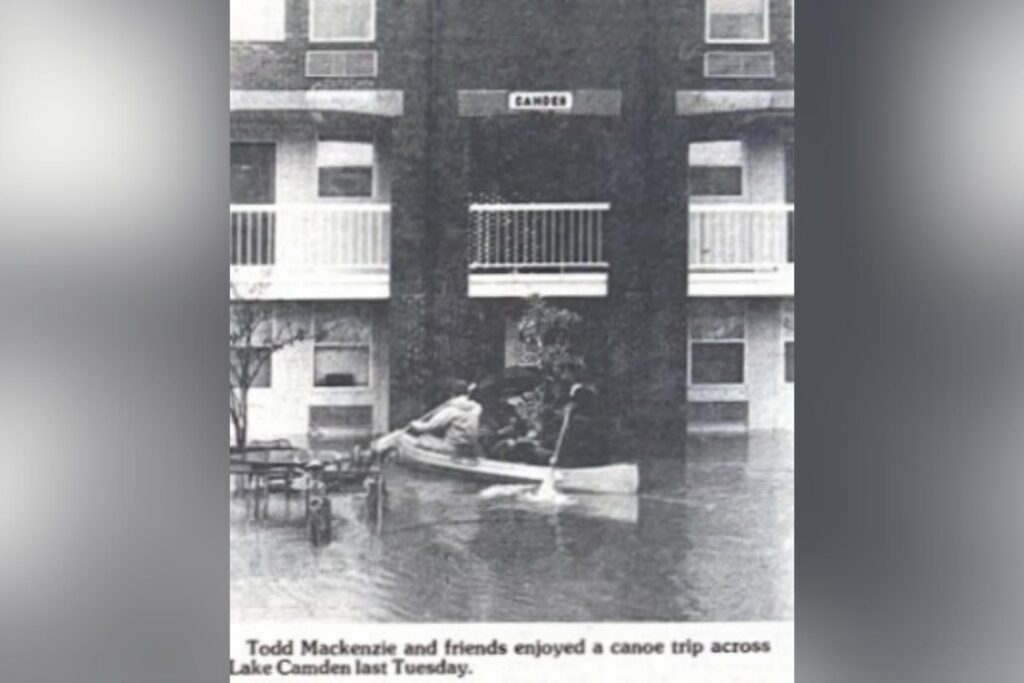

In Wood County, where estimates show the number of people staying outside has risen in recent years, the Parkersburg City Council has responded by passing an ordinance prohibiting public camping. Amid an uptick in Wheeling, city officials are considering a similar ordinance and recently almost evicted several dozen people in an encampment.

Before becoming homeless, McCumbers, who is in long-term recovery, was working to improve her quality of life by taking college classes in counseling using her phone. She had to stop after moving outside with her husband and losing WiFi.

“We’re really trying,” she said.

Now she’s waiting for doctor clearance, due to knee surgery, to find work. Without access to medications for an intestinal disorder, she thinks she’ll end up in the hospital.

Parkersburg wants to ‘compel’ people into shelters. There’s not room

Parkersburg Mayor Tom Joyce said the new law, which establishes a fine of $100 to $500, is intended to get people into shelters and connect them to programs like mental health and substance use treatment. He said along with providing bus tickets out of town, the city also has homeless coordinators.

“I think there should be some manner in which we kind of compel them to get the help that they need,” he said.

But while Parkersburg has more than 100 shelter beds, most are full, and the few remaining beds aren’t enough for the city’s homeless population.

The Salvation Army, which has about 40 beds, operates at capacity. The larger Latrobe Mission has around 80 beds, mostly full, but a shelter official said they’d try to make room if they saw a sudden large influx due to the ordinance. But even if more beds open, rules to entry, such as a requirement for photo ID, would prevent many of those sleeping outside from staying there.

The House to Home day shelter, which provides people experiencing homelessness with amenities like laundry machines and showers, saw about 250 people who are homeless last month — about twice the total number of shelter beds in Parkersburg.

Sarah Towner, director of the day shelter, said that was an increase of about 100 people compared to the month before.

“They’re not allowed anywhere,” she said. “On the sidewalk, in the woods. I don’t know what they expect them to do.”

According to Parkersburg officials, there had not been any citations issued, as of several weeks after the ordinance passed, for violating the camping ban.

But McCumbers said she’s already worried fines will make it harder to find housing, and that the city is taking other steps to force people to go to the shelters. She said city workers tore down their tent a few weeks ago, then those workers called shelters looking for beds for the couple, another unsuccessful effort.

“And they said they were here to help,” McCumbers said.

Wheeling following suit with punitive measures before effective assistance

Nearly a two-hour drive north of Parkersburg, city officials in Wheeling have also been getting stricter with the homeless population after taking steps to reduce homelessness in recent years.

It started last month when city workers, under the direction of City Manager Robert Herron, told 30-50 people who live in tents in a wooded area on the East Wheeling hill that they would be evicted in two weeks. Herron didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment, but he told WTRF that petty crime had increased at the encampment.

Kate Marshall, a leading organizer, said city officials previously directed people who are homeless to leave other encampments and stay on the hill instead.

So because they thought their presence there was city-sanctioned, residents decorated their spots, turning tents into homes. They’ve built footpaths leading to each residence. One spot had a picture of Jesus.

Todd Jones, a veteran with PTSD, stays on the East Wheeling hill near some other tents. He doesn’t want to be packed in at a shelter.

“Too many people around me, I get highly anxious,” he said.

The day before the eviction was planned, organizers held a hours-long protest across from City Hall, calling for it to be postponed. Many signs asked where the homeless would go.

Wheeling officials ended up pausing the eviction, saying that it may not take place at least until a warming center opens in mid-December. But because they didn’t announce that pause until the last minute, the situation had already been hard on hill residents, many of whom had spent the previous two weeks packing up their possessions into totes and piles.

Just days later, Wheeling officials took the first step towards following Parkersburg’s lead, and enacting their own ordinance.

Last week, city councilors in the “Friendly City” introduced a bill that would ban public camping. Like Parkersburg, it would enact $100 to $500 fines for sleeping in public spaces like rights-of-way or parking lots.

Following widespread criticism from the community, city councilors noted during the meeting that the city already provides funding to local nonprofits. They said they would support a managed camp, where service providers would visit to provide housing assistance, mental health services and drug treatment.

Councilman Ty Thorngate suggested eliminating the fines in the ordinance and replacing them with a community service assignment. The original proponents, Councilman Ben Seidler said they had to represent housed constituents as well, referencing defecation and needles for drug use in public, and Councilman Jerry Sklavounakis, who brought up the idea, added that he was in support of a low-barrier shelter.

The city council meets again Nov. 7 and could consider the camping ban.

It’s not just a lack of beds

In Wheeling, there are three night shelters, but one, operated by the YWCA, is only for people who have been the targets of domestic violence.

And like those in Parkersburg, the other two shelters are already turning people away.

Connor Morrison, a homeless shelter technician, said he regularly has to deny entry due to limited capacity at Northwood Health Services’ 24-bed shelter. Lt. John Lawrence of the Salvation Army said its shelter has a handful of open beds, although renovations are in progress to expand it.

But among the other barriers to staying in shelters include random drug tests, drug tests upon entry, background checks and ID requirements.

Problematic drug use can be a contributor to homelessness, but some of those who are homeless also turn to substance use to cope, and people who live outside often lose their belongings, such as IDs or other identifying documents, to theft.

The city has been working with the Wheeling Housing Authority to open a lower-barrier shelter that would have fewer rules, but that shelter is a long way from coming to fruition.

Mark Phillips, CEO of Catholic Charities West Virginia, which offers a day shelter in Wheeling, said a new shelter with fewer rules would “meet people where they are.”

“If you’re building additional barriers to these folks for shelter, you’re just always going to have a population of people that can’t live inside,” he said.

The new shelter wouldn’t require ID, for instance, although people actively using drugs wouldn’t be permitted. But Joyce Wolen, executive director of the Wheeling Housing Authority, said it lacks funding and noted that grant-writing is a long process. She also said that finding affordable housing is a major challenge to address homelessness in the city.

A shortage of affordable housing units was one of the largest problems identified in a 2015 state plan to end homelessness in West Virginia. The state has made some progress but key policy changes haven’t been enacted and people are still living outside in cities like Parkersburg and Wheeling.

Misty Gilmore, one of the hill residents who attended the protest against the eviction, said she wished more of her neighbors had come to the event, but that some were experiencing dissociative states of mind, making it hard for them to face reality, and some were packing up.

She said it was hard to get back on her feet after leaving an abusive relationship. The mental effects still linger, but it helps to make others happy, so she works to cheer people up at the encampment.

She hasn’t attempted to find one of the limited shelter beds because somebody else might have kids or need it more.

“Some people have bigger problems than I do,” she said.

Tears welled up in her eyes when asked if she knew where she’d go.

“I have no clue,” she said.

Reach reporter Erin Beck at erin@mountainstatespotlight.org.